In the world of material handling and industrial machinery, the selection of the right chain is a critical decision that impacts efficiency, safety, and operational costs. Free flow chains, known for their smooth, low-friction operation on accumulation conveyors, are a common sight in packaging, bottling, and light assembly. But a persistent question arises among engineers and plant managers: Can these chains reliably perform in heavy-duty applications? This article will provide a detailed, balanced examination of free flow chains, exploring their design, inherent strengths, limitations, and the specific conditions under which they might—or might not—be suitable for demanding tasks. The goal is to move beyond marketing claims and offer a practical, engineering-focused perspective.

Understanding Free Flow Chain Design

To answer the question, we must first understand what a free flow chain is. Unlike a standard roller chain designed primarily for power transmission, a free flow chain is engineered for low-pressure accumulation conveying.

Its key design characteristics include:

- Low-Friction Rollers: These are the heart of the system. The rollers are typically made from engineered polymers (like acetal or nylon) or are metal rollers with special bearings. They are designed to rotate freely with minimal resistance when a load is stationary on them.

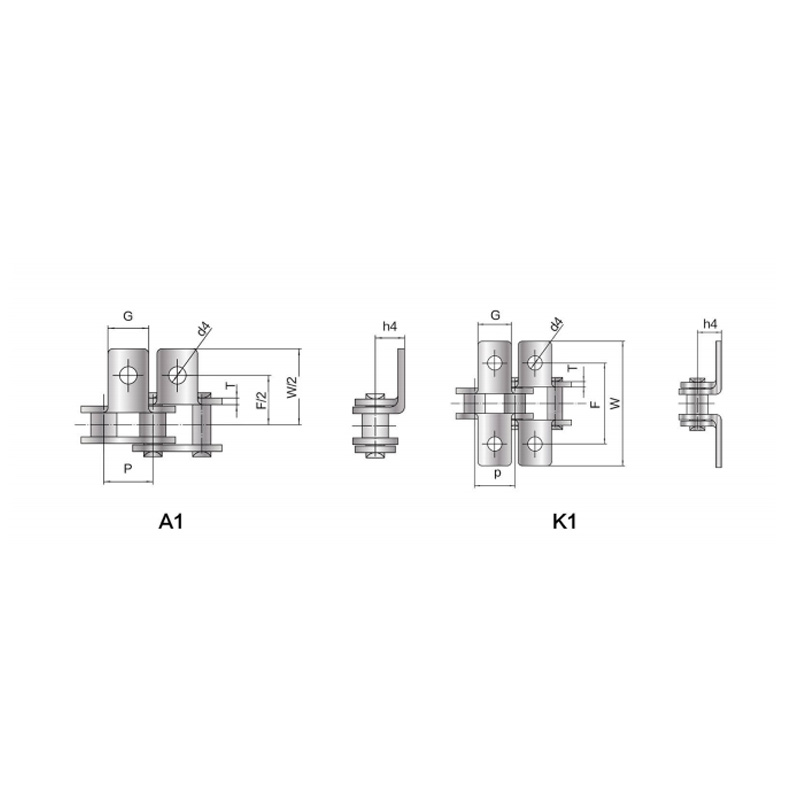

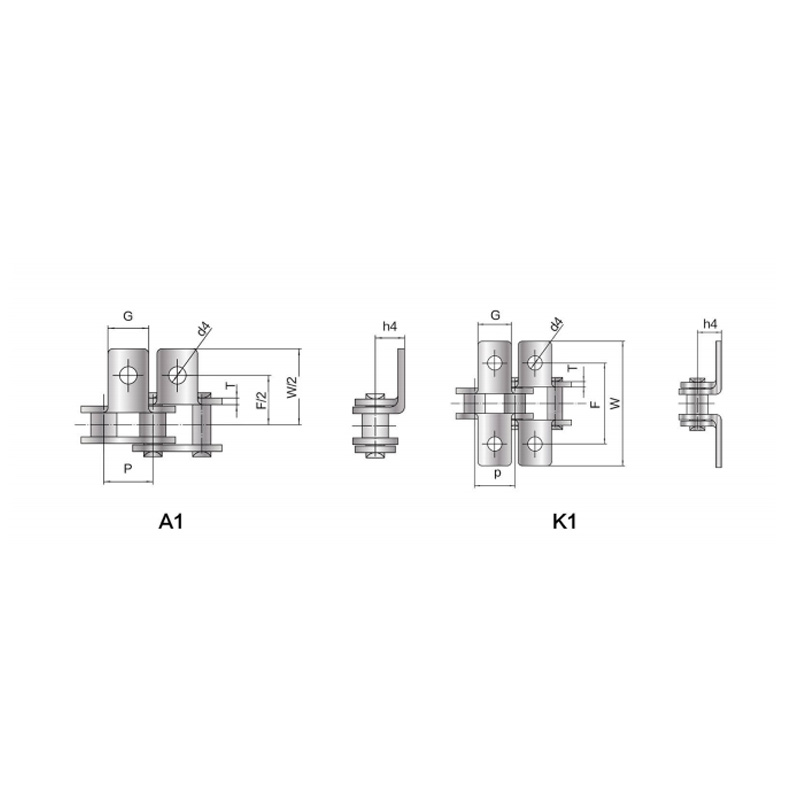

- Multi-Tier Roller Arrangement: The chain often features two or more rows of rollers set at different heights. The top tier (“conveyor rollers”) contacts and moves the product, while the lower tiers run on the conveyor track, enabling the chain to navigate corners and curves smoothly.

- Accumulation Function: The core purpose. When a product on the conveyor is stopped, the chain rollers simply spin beneath it without creating drag or requiring the entire conveyor line to halt. This prevents product damage and allows for zoning in assembly processes.

This design prioritizes smooth product handling and accumulation over high tensile strength or impact resistance.

Defining “Heavy-Duty”

“Heavy-duty” is a broad term. For clarity, we must define it in operational contexts:

- High Load Weight: Consistently handling unit loads exceeding 100 lbs (45 kg) per foot of chain, or palletized goods weighing 1,000+ lbs (450+ kg).

- High Tensile Load: Applications where the chain itself is under significant pulling force, such as inclined conveyors or long center-distance drives.

- Harsh Environments: Exposure to extreme temperatures, moisture, corrosive chemicals, abrasive dust, or frequent washdowns.

- High Impact or Shock Loading: Applications where loads are dropped onto the chain or where starting and stopping is sudden and jarring.

- Continuous, High-Cycle Operation: Running 24/7 with minimal downtime, as in mining, heavy manufacturing, or bulk material handling.

The Case Against Traditional Free Flow Chains in Heavy-Duty Roles

For most classic heavy-duty applications, a traditional polymer-roller free flow chain is not the optimal choice, and often a poor one. Here’s why:

- Material Limitations: Polymer rollers, while excellent for low friction and quiet operation, have lower compressive strength and wear resistance than hardened steel. Under constant heavy loads, they can deform, crack, or wear prematurely.

- Bearing Capacity: The small bearings within free flow rollers are designed for the radial load of the product above, not for the high tensile loads of pulling massive weight over a long distance. They can fail under excessive side pull or tension.

- Structural Integrity: The chain plates and pins of a standard free flow chain are not typically designed to withstand the same tensile stresses as a heavy-duty drive chain (like an ASME/ANSI series 80 or 100). Using them in high-tension applications risks chain stretch, pin shearing, or catastrophic failure.

- Environmental Vulnerability: Polymers can degrade under UV light, become brittle in extreme cold, or soften in high heat. They are also susceptible to certain chemicals. In wet or dirty environments, contaminants can ingress the roller bearings, causing seizing.

- Impact Resistance: The sudden load of a heavy metal casting or pallet can shatter polymer rollers or damage the internal bearing assembly.

Where the Line Blurs: Specialized and Hybrid Solutions

The answer is not a simple “no.” Engineering advancements have created specialized categories of free flow chains that push into medium- to heavy-duty realms. The key is matching a specifically engineered product to a well-defined application.

- Metal-Roller Free Flow Chains: These replace polymer rollers with steel or stainless steel rollers, often equipped with high-capacity precision bearings. This dramatically increases load capacity, wear resistance, and temperature tolerance. They can handle heavier unit loads and are suitable for washdown environments (in stainless versions). However, they are still primarily for conveying, not extreme tensile loading.

- Combination/Engineered Class Chains: Some manufacturers offer chains that marry free-flow functionality with the tensile strength of a drive chain. These might use heavier side plates, larger pins, and bushings, and incorporate free-flowing rollers. They are designed for applications requiring both significant pulling power (e.g., on an incline) and accumulation.

- Application-Specific Designs: For industries like pallet handling, chains are built with larger, hardened rollers and reinforced structures to handle the point loads of pallet boards. These are “heavy-duty” within the specific context of unit handling.

Practical Guidelines for Evaluation

If you are considering a free flow chain for a demanding application, follow this structured evaluation:

- Consult Manufacturers Early: Engage with application engineers from reputable chain companies. Provide exact data: maximum load weight, load distribution (point load or uniform?), conveyor length and incline, cycle rate, and environmental conditions.

- Decouple Tensile and Load Requirements: Analyze them separately.

- Tensile Requirement: Calculate the total pulling force needed (including friction, incline, and acceleration). Compare this to the chain’s ultimate tensile strength (UTS), applying a significant safety factor (e.g., 8:1 to 10:1 for continuous operation).

- Load Capacity: Look at the manufacturer’s dynamic load rating for the rollers. Ensure the weight per roller or per foot of chain is within spec. Remember that impact loads require a much larger margin.

- Consider Total Cost of Ownership (TCO): A heavier-duty chain has a higher initial cost but may offer far longer service life, reducing downtime and replacement costs. Calculate TCO, not just purchase price.

- Pilot Testing: If possible, run a sample of the selected chain in a real-world or simulated environment. Monitor for wear, deformation, and bearing performance.

Conclusion: A Qualified Answer

So, can free flow chains be used for heavy-duty applications?

For traditional, extreme heavy-duty applications—such as mining, forestry, heavy incline conveying, or handling massive, shock-inducing loads—standard free flow chains are unsuitable and potentially dangerous. In these realms, dedicated heavy-duty drive and conveyor chains are the unequivocal choice.

However, within the spectrum of unit handling and accumulation conveying, the definition of “heavy-duty” has expanded. Through the use of metal rollers, reinforced designs, and hybrid engineering, modern free flow chains can reliably perform in medium- to heavy-duty applications such as:

- Pallet handling in distribution centers.

- Loads up to several hundred pounds per foot in manufacturing.

- Accumulation systems in washdown-ready food processing (using stainless steel versions).

- Applications requiring both conveying force and zero-pressure accumulation.

The final verdict rests on precise application engineering. By abandoning a one-size-fits-all mindset and rigorously analyzing load, tension, environment, and duty cycle, you can determine if a specialized free flow chain is a robust and efficient solution or if a different chain technology is necessary. Always prioritize specifications and verified data over general categorizations, and when in doubt, err on the side of over-specification for safety and longevity.